Sep 03 2019.

views 1341Her petite figure and infectious smile can be deceiving until you start having a conversation with her. She is Kavindya Thennakoon, a positive change-maker that looks at solving problems in a practical way, especially when it comes to education. She describes herself as an education designer as she likes to design education tools that could be implemented in a classroom. According to her, education lies at the core in changing the game for any human being. Kavindya has many feathers in her hat – from advocating on education to community development to gender equality and many other areas. Thennakoon won two awards – Harvard Global Trailblazer Award and the Queen’s Young Leader Award for pioneering a community development project titled ‘Without Borders’ which she started with her friend Sakie Ariyawansa back in 2014. She recently graduated with a major in Anthropology and a minor in Cinema and Media Studies from Wellesley College.

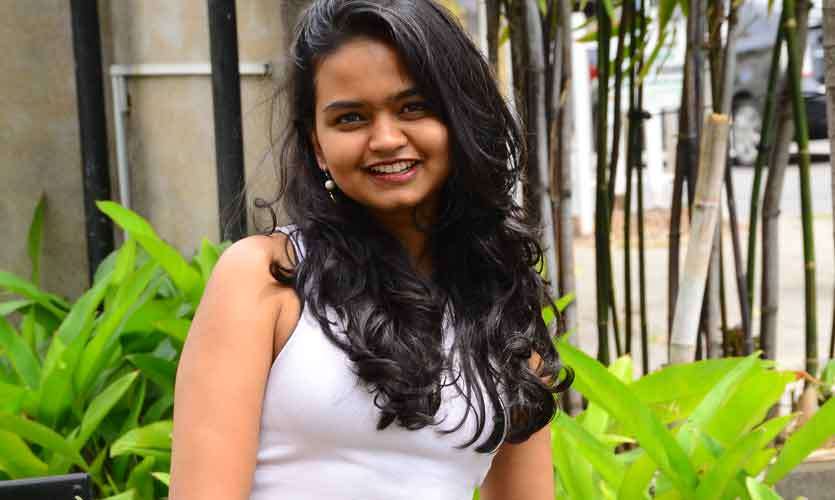

Gracing this month’s W@W cover is the young and energetic Kavindya herself, who sheds light on the journey she has come this far, her inspirations, experiences and challenges in life.

What do you do at the moment?

I started ‘Without Borders’ before I went to college. I knew that I was always passionate about education and design and wanted to bring these two disciplines together. ‘Without Borders’ started in 2014 and we have been running since then. We run four centres in Deraniyagala, Maradana, Ranamure and Galle. We try to see how a design perspective can be used to create innovative learning tools and technologies that are applicable to local classrooms. Therefore, we work with teachers and classrooms and see how to get the best out of the space and resources we have in order to create a new learning experience for teachers and students.

You recently graduated with a major in Anthropology. Any particular reason why you chose that subject?

I had no idea what anthropology was. I was following an Economics track for about two years and I took a class on digital storytelling and visual ethnography, and found it very interesting. It was about understanding why people do the things they do, say the things they say and feel what they feel. Then I realised that that was what I always wanted to do. Then I was head-hunted for a large financial institute - but I didn’t enjoy that programme at all. So I came back clueless about what I should do with my life. I realised that I have been doing something that I hated for two years, simply because I wanted to make things financially better for myself and my mother. After realising this, I dropped my Econ major the next day and changed to Anthropology. Everything that we do boils down to deeply understanding human experiences and therefore, doing Anthropology made complete sense.

You were interested in community development at a very young age. How did that come about?

There were three influences for that. I grew up listening to my father’s story – he was the chief jailer at the Welikada Prison and was killed in 1997. But I still hear people talking about him and how much of an influence he has been in their lives. He came from an ordinary family and was a public servant but made such an impact on people’s lives, mainly prisoners. What he always said was that if this country needs to be fixed, the prisons need to be fixed first. He did a lot to combat the drug trade which was a menace during the time, which was also why he was killed. So the idea of standing up for what you believed in irrespective of the cost, was put into my head from a young age. As in the case of my mother, she lost so much in her life within a short period of time but I grew up seeing how she dealt with society, how she did exactly what she wanted to do. Even after all that, she still had time for others. Despite not having much herself, I remember how she once gave the only sewing machine she had to a young woman in our village who was struggling with three kids and a husband who was a drug addict. I think from a young age she taught me how choice and not charity is the solution.

When I was seven I joined the Sri Lanka Girl Guides Association (SLGGA) and I have been around very strong women who knew they had a role to play and the power to change the country.

Was that how you were inspired to help children as well?

If there was anything that changed the game for me, it was education. I always believed that if we fixed our classrooms all these other problems we talk about -from drug abuse to child abuse and sexual violence to the political situation could be fixed.

Tell us about your experiences while working with children at grass-root level..

I have seen that we have amazing potential in both our students and teachers because we have grown up battling numerous problems. If you talk about problem-solving or critical thinking, we are inherently good at both. Beyond Colombo, you will come across children who are very creative and can make brilliant things out of limited resources they find at home. I think the problem is that our schools are geared towards the few number of spots we have within our local university system. This means that the only thing we measure is how well you are able to memorise something and put it onto paper within a period of three to four hours. That leaves out more than half the population of students who are skilled in other areas besides memorising something and rote learning. I think that needs to be fixed. There should be better coordination between our teacher-training arm, the Ministry of Education and the Examinations Board. Most of our curricula are good, for example the English textbooks that we work with have been modified and they look interesting and relevant to the emerging world. But the problem lies in the fact that our teachers are not adequately trained and lack the needed resources to deliver the content. So we need radical change-makers to work at a ministerial level and to go into the local administration process.

How was your experience at SLGGA with Stop the Violence campaign?

I joined the programme through the guidance of my wonderful mentor - Mrs Marlyn Dissanayake; past Chief Commissioner of the SLGGA, just after school and was training children who were my age. Sri Lanka doesn’t have a comprehensive sexual and reproductive health curriculum. If you look at cases around sexual abuse, in most incidents the perpetrator is within the family. Incest is a huge problem here. So if you look at the dark figures, we have children abused by their father, grandfather, an uncle or someone who comes from a place of trust. Secondly, abuse is prolonged and it happens to the extent that a child doesn’t know whether it’s alright or not for her father to touch her inappropriately. In every case of abuse that you see, I feel that the education system is to be blamed. If a classroom teaches the Pythagoras theorem and the periodic table but fails to teach kids about their own bodies and differentiating between good and bad touch, then it’s truly ironic. When a case is reported it is usually referred to the Women and Children’s desk at the Divisional Secretariat for case management and although there are phenomenal public servants working there, they have 60-70 cases to handle in a month. We always talk about gender-based violence within the context of women but we don’t realise that there are men who are also victims. This also means we merely talk specifically to women and fail to address the perpetrators. So we should shift the way we talk about these cases.

Before ‘Without Borders’ reached five years you won a Queen’s Young Leader Award and Harvard.. How do you feel about that?

Those were important to us because they came at an earlier stage when we were a young, all-female team. We had all qualified people and they happened to be female. Even now when I go into a government office there’s scepticism because I’m a female. I look visibly young, so awards like that helped to validate the work we were doing. But after three to four years we realised that the best form of validation comes from within the community itself; getting feedback from those whom we have trained and seeing them implement what we taught was what really mattered.

What’s the most satisfying part about the work you do?

Especially when you work with teachers and children, and to see them realising their untapped potential to change themselves and the communities around them is a truly special feeling. I've had the distinct honour of seeing some of my own students becoming community teachers themselves and I think there is nothing more satisfying than to see them achieve much more than you have.

The most challenging…

This sort of work is difficult. It’s long drawn. If it's to be sustainable and impactful it requires immense patience and grit. So someone has to have the capacity to be with it for five years or more. It’s tedious work but at the end of the day it’s nice to see that someone has changed their life trajectory because of your work and that is a nice feeling.

Future plans..

I’m heading for my Master’s in September. It’s a programme that I followed since we started ‘Without Borders’. When we initially started, we used a lot of their tools in the classroom. The programme is called LDT – Learning, Design and Technology at the Stanford School of Education, California. It’s an year-long programme where they try to bring design and technology as two fields and rethink how we approach learning and education. I’m excited to see what’s happening there within the edu-tech space and to see what we can bring back here.

Pics by: Waruna Wanniarachchi

1 Comments

Dhushan Ekanayake says:

Jul 19, 2024 at 12:19 pmVery impressed with your interview/write up about Kavindhya in W@W mag. I teach Business English at a private university in Germany and so much of what Kavindhya said resonates totally with me. As I’m already 72 years old, I don’t feel capable of actually being hands on in helping develop youngsters, but I do a lot of English proof reading at my uni, amongst other things. I’d gladly help out for free if you/Kavindhya/tilli etc. need my services. I live in Germany, but working online makes such projects easy. Let me know please.