Jan 13 2026.

views 406By Rihaab Mowlana

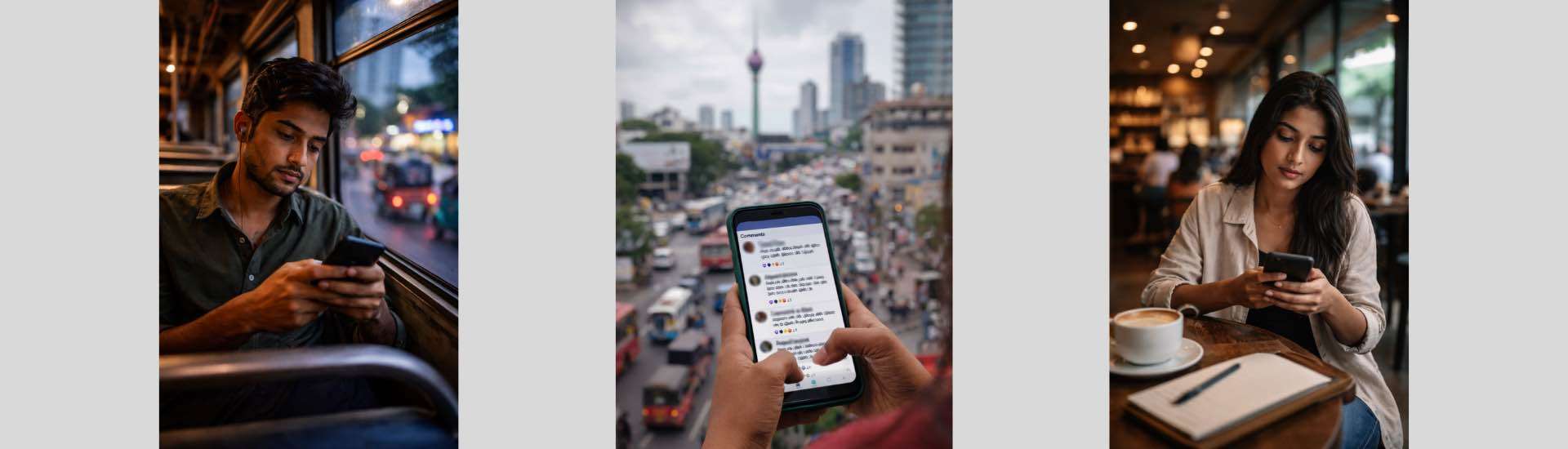

There was a time when a truly nasty comment online still caused a pause. Someone would call it out. Someone would say this is too much. Someone would at least acknowledge that a line had been crossed. Now it just blends into the feed, sandwiched between memes and news updates, ordinary enough to scroll past without thinking twice.

We like to pretend the internet suddenly got worse. That something snapped. That discourse collapsed overnight. But most of what we are seeing now did not appear all at once. It settled in slowly, becoming familiar enough that cruelty stopped feeling like a problem and started feeling like the price of being online.

In Sri Lanka, this shift is hard to miss. Scroll through any political post, and you will see how quickly things turn personal. Not critical. Not analytical. Personal. Bodies, language, sex, worth. The escalation is fast and predictable, and what is more unsettling than the comments themselves is how little they surprise us anymore. Cruelty has not become louder. It has become easier.

When Being Mean Became the Fastest Way to Get Noticed

Social media rewards reaction, not reflection. The sharpest comment floats to the top. The cruellest joke gets the most engagement. The angriest take travels furthest. Over time, this trains behaviour. People stop trying to make a point and start trying to land a hit.

Politics thrives in this environment. Complex issues do not perform well online. Insults do. Humiliation does. Reducing a person to a punchline does. Somewhere along the way, argument was replaced by performance, and cruelty became a shortcut to relevance.

This is not just a Sri Lankan problem. Globally, studies by organisations like the Pew Research Centre have shown that hostile political content spreads faster and wider than measured discussion. Platforms are built to reward intensity. Nuance does not stand a chance.

But in Sri Lanka, where political conversations are already charged with history, frustration, and distrust, the result is particularly ugly. Comment sections feel less like debate and more like release valves. Anger spills out unchecked. And cruelty, once it proves effective, gets repeated.

Politics Didn’t Create This, But It Benefits From It

Political critique is necessary. Anger can be justified. Dissent is healthy. None of that is the problem.

The problem is how easily criticism slides into something else entirely. Sexualised remarks framed as jokes. Attacks on appearance passed off as commentary. Threats softened by sarcasm. When called out, these are defended as passion, humour, or the rough-and-tumble nature of politics.

Women in public life experience this most visibly. Their politics are debated through their bodies. Their credibility is undermined through sexualised language. The expectation is not safety, but resilience. If you choose visibility, you are expected to absorb the abuse quietly.

This is not unique to Sri Lanka. Amnesty International has documented how online harassment disproportionately targets women and marginalised voices in politics across the world, pushing many to disengage entirely. The abuse is rarely framed as violence. It is treated as background noise.

In Sri Lanka, that normalisation has consequences. When cruelty becomes routine, fewer people are willing to step into public discourse. Not because they lack opinions, but because the cost of expressing them feels too high.

The Distance That Makes Everything Worse

Screens make cruelty feel abstract. You do not see the reaction on someone’s face. You do not hear the silence after a comment lands. You do not witness the accumulation of harm.

This distance changes behaviour. People say things online they would never say out loud. Not because they believe them more strongly, but because the consequences feel diluted.

Responsibility spreads thin in a crowd. Pile-ons form without anyone feeling fully accountable.

Globally, researchers have linked prolonged exposure to hostile online environments with increased anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and withdrawal from public participation. When cruelty becomes the dominant tone, people do not toughen up. They disappear.

You see this play out locally all the time. Accounts go quiet. Opinions soften. Voices retreat into private group chats where things feel safer. Silence is mistaken for apathy, when it is often just self-preservation.

The Free Speech Argument, Selectively Applied

Cruelty online is frequently defended using the language of free speech. The argument is familiar. If you cannot handle it, stay offline. If you choose to speak publicly, expect backlash. This is just how the internet works.

What is rarely acknowledged is how selectively this logic is applied. Free speech is defended fiercely when it protects cruelty, but far less enthusiastically when it comes to protecting people from harm. Nuance is mocked as weakness. Empathy is dismissed as censorship.

Globally, the United Nations has flagged online gender-based violence as a growing barrier to participation in public life. When abuse is framed as speech rather than harm, responsibility disappears. The space becomes hostile by design.

In Sri Lanka, this selective defence of free speech has narrowed discourse. Loudness is mistaken for courage. Cruelty is mistaken for honesty. And those who opt out are framed as fragile rather than exhausted.

What Casual Cruelty Is Doing to Us

The most damaging effect of all this is not the loud moments, but the quiet erosion. The scrolling past. The shared joke that feels wrong but still gets shared. The way we lower our expectations of how people should be treated, especially online.

Over time, cruelty stops feeling like a violation and starts feeling inevitable. We adjust. We disengage. We stop expecting better. And when expectations drop, behaviour follows.

This affects more than politics. It changes how we relate to each other. How we disagree. How we listen. Public discourse becomes narrower, harsher, and more performative. The internet becomes a place where being thoughtful feels risky and being cruel feels efficient.

Media scholars have warned that this erosion of discourse weakens democratic participation. When political conversation feels hostile, people stop engaging. Not because they do not care, but because caring feels like walking into a fight you did not sign up for. Sri Lanka, already tired from crisis and uncertainty, cannot afford that kind of disengagement.

Sitting With the Uncomfortable Truth

None of this means disagreement should disappear. It should not. Criticism matters. Anger has a place. Politics is not meant to be polite. But cruelty does not need to be the default setting. And right now, it often is.

The internet reflects us, but it also trains us. What we engage with rises. What we tolerate becomes normal. Casual cruelty thrives not because everyone is cruel, but because it is easy, rewarded, and rarely challenged.

We can keep pretending this is just how things are now. Or we can admit that something has shifted, and not in a way that serves us.

Maybe the problem isn’t that people are being cruel online. Maybe it’s how easily the rest of us have learned to live with it.

0 Comments