Nov 07 2025.

views 116By Panchali Illankoon

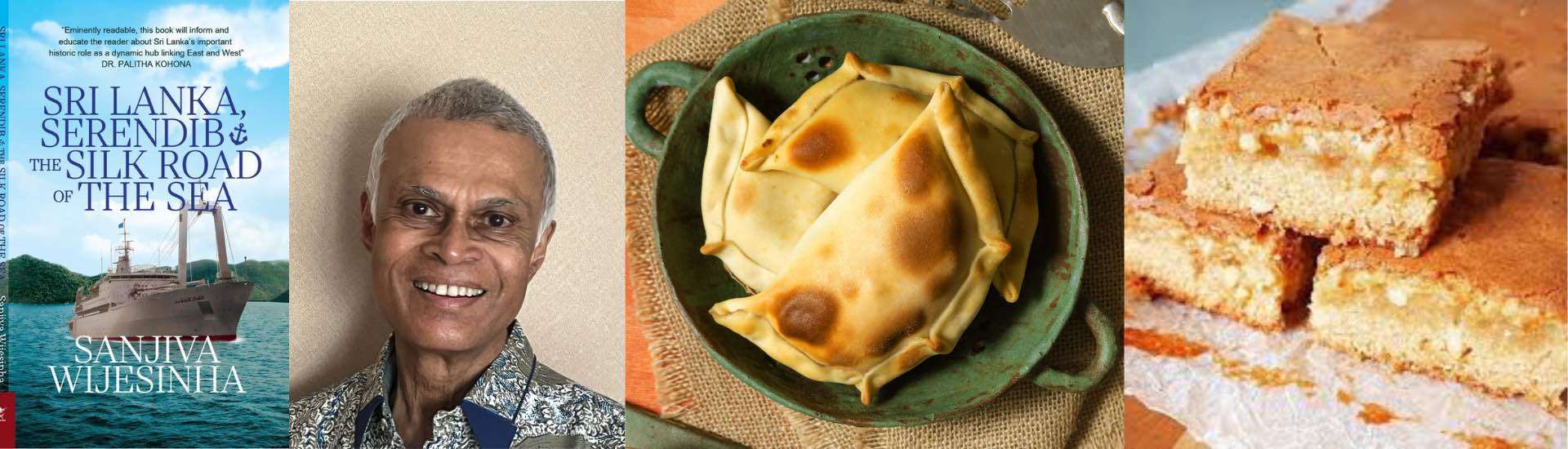

Dr Sanjiva Wijesinha traces the trade journeys that made Sri Lankan cuisine what it is today in his new book, ‘Sri Lanka, Serendib & The Silk Road of the Sea’.

When Condé Nast Traveller named Sri Lankan cuisine the seventh-best in the world in its 2025 Readers’ Choice Awards, few were truly surprised. After all, Sri Lankan food has been in the limelight for years now – in 2019, the BBC Good Food team named it the No.1 trending cuisine of the year. But long before the magazine accolades, this island’s food told a far older story to its travellers, one of spice routes, maritime history and colonisation that built centuries of exchange between us and the world. It's a story Dr Sanjiva Wijesinha brings to life in his latest book, published by Perera-Hussein Publishing House, ‘Sri Lanka, Serendib, and the Silk Road of the Sea’ where he unpacks the little-known subject of Sri Lanka’s maritime past and its central role in the Maritime Silk Road.

In the chapter titled ‘Foods That Crossed the Seas’, Dr Wijesinha delves into the essence of Sri Lanka’s culinary heritage and uncovers elements of a cuisine that has been shaped by centuries of trade, exchange and connection. The chapter begins with him recalling an evening in Oxford many years ago, hosting friends for a Lankan meal prepared by his wife, when a colleague asked why Sri Lankan food seemed “so much better” than other cuisines of the Indian subcontinent. His question was answered by another Sri Lankan at the table who quipped that there’s simply no comparison: “the rest of South Asia has food, we in Sri Lanka have cuisine!”.

Dr Wijesinha concedes that there’s an element of truth to this statement. When the book came together quite incidentally after he delivered the 2024 Victor Melder Lecture in Melbourne, Australia, on Sri Lanka and the Silk Route, while speaking about the many different people who came into the island, he realised how often his audience connected those migrations to the food they brought with them. Sri Lankan cuisine, he explains in conversation, was never born in isolation. “Any time you go to another country, you still want to eat the food you are familiar with,” he compares. “Back then, when people travelled across seas to different countries, they had to stay put and wait for months between monsoon seasons before they could sail again. In that time, they would have cooked their own food, substituted ingredients with whatever was available locally and eventually shared those recipes with the people they lived among.”

There are many dishes we enjoy today that stand in testimony to this statement. As Dr Wijesinha aptly identifies-rice preparations from the mainland to the north, exotic and pungent spices from Indonesia and the Malay peninsula, sweets made with honey and rosewater with the arrival of Muslims from West Asia and the festive favourites of Love Cake and Breudher from the Europeans.

Perhaps none illustrates this global mingling of recipes better than the Sri Lankan short eats that we love so much. Dr Wijesinha writes that what we fondly call ‘pattis’ in Sri Lanka is Iberia’s ‘empanadas’, India’s ‘samosas’, Jamaica’s ‘patty’ and Brazil’s ‘pasteis’. The Sri Lankan pattis, semi-circular with a crimped edge, shares its name and style with the Jamaican patty, yet its filling resembles the spiced potatoes and meats of the Indian samosa. “It seemed that wherever the Silk Route followed, so did the samosa”, shares Dr Wijesinha, describing the linguistic crossovers of the snack, which is also known in Arabic as ‘sambozec’ and in Persian as ‘sambozac’. “It’s all too possible that we learned to make our pattis from the Portuguese but adopted the filling from samosas in India to match our local palate.”

But not all names are what they seem. Take the crispy, crunchy Chinese rolls, which, as Dr Wijesinha laughs, “has nothing to do with the Chinese at all.” In his book, he questions how the Chinese rolls came to be. The only connection it has to China is that it shares the same cylindrical form as a spring roll, but that’s where the commonalities end. If it’s similarities one is looking for, then the crepe-wrapped, breadcrumbed, deep-fried Lankan roll owes just as much to the croquets de carne or rissoles from Portugal and Holland. While acknowledging that it’s entirely possible that these snacks evolved independently in their respective lands, Dr Wijesinha leaves readers pondering on the intriguing possibility that somewhere along the Silk Route, it’s all linked together.

And if the island’s savouries are evidence of the trade history of Sri Lanka, then our festive sweets point to decades of colonisation – Love Cake, first introduced during the 16th century by the Portuguese as bolo d’amor, Breudher with its Dutch roots, and the rich, indulgent Christmas Cake brought by British colonisers that has since evolved into something quintessentially local. What makes Dr. Wijesinha’s book an engaging read is that while he draws parallels between Sri Lankan cuisine and its foreign influences, he doesn’t insist on making them a rigid fact. As he writes about why Love Cake is given its moniker, he wonders whether it’s because it’s a labour of love to make or because it was made to win someone’s heart. “Who knows?” he concludes in the book, “One should never let the truth stand in the way of a good story.”

One of the most charming anecdotes in Foods that Crossed the Seas is Dr. Wijesinha’s visit to Oman during the 1990 UNESCO Maritime Silk Route Expedition – a study trip conducted from 1990-1991 with the participation of 100 professionals and 45 journalists from 34 countries travelling 27,000km from Venice, Italy to Osaka, Japan studying the maritime trade routes connecting the East and the West. Dr Wijesinha, who was working as a paediatric surgeon at the children’s hospital in Colombo, was one of four people from Sri Lanka who joined the expedition. On his leg of the journey, he visited several ancient ports of the Indian Ocean – Alexandria in Egypt, Muscat, Salalah and Samharam in Oman, Gopakapattinam and Goa in India and Barbarikon in Pakistan.

During a stopover in the Omani capital Muscat, Dr Wijesinha met Moosa, an Omani scholar who invited him to share a meal and spend an evening with his family at his home, particularly to enjoy dates and halwa after dinner. That evening, after a leisurely meal, Moosa served a sweet, soft, gelatinous Omani Halwa that bore a striking similarity to a long-loved dessert back home in Sri Lanka called ‘Muscat’. “The proverbial penny dropped”, writes Dr Wijesinha, when they both realised that it was, in fact, the same sweet known by different names – probably named after the people who sailed to Sri Lanka from Muscat and brought this sweet treat along.

The question that naturally arises as one reads through this chapter is that if so many of what we call authentic Sri Lankan foods are really not truly of Sri Lankan origin, can we still call it “authentic?” “There’s nothing purely authentic about any cuisine,” comments Dr Wijesinha, “Even the British consider Indian takeaway as one of their staple foods nowadays. Every cuisine has been influenced by some other cuisine along the way, but they have their own local touch. That’s what makes it authentic.”

Tracing these influences, however, demanded more than what academic texts could offer. “Old aunties,” laughs Dr Wijesinha when asked what sources he referred to for this chapter. He credits Deloraine Brohier’s A Taste of Sugar & Spice (2012) and Charmaine Solomon’s cookbooks as valuable references, but says it was often the wisdom of “old aunties who knew stories and little anecdotes about the history and origin of each dish” that proved most insightful. “Once you get interested in a topic, there’s a lot of information to be found.”

This sentiment echoes the engaging curiosity that runs throughout Sri Lanka, Serendib, and the Silk Road of the Sea and reminds readers of the role Sri Lanka played in the fascinating network of trade routes that connected the East and the West. As Dr Wijesinha concludes in the chapter, “One does not have to peruse ancient tomes or learned articles in academic journals to find out about the past. One simply needs to have an open mind and spend time in conversation with other like-minded human beings. We will learn from each other what we each know - and sometimes things that we do not know that we know.”

0 Comments