Sep 02 2025.

views 17By Rihaab Mowlana

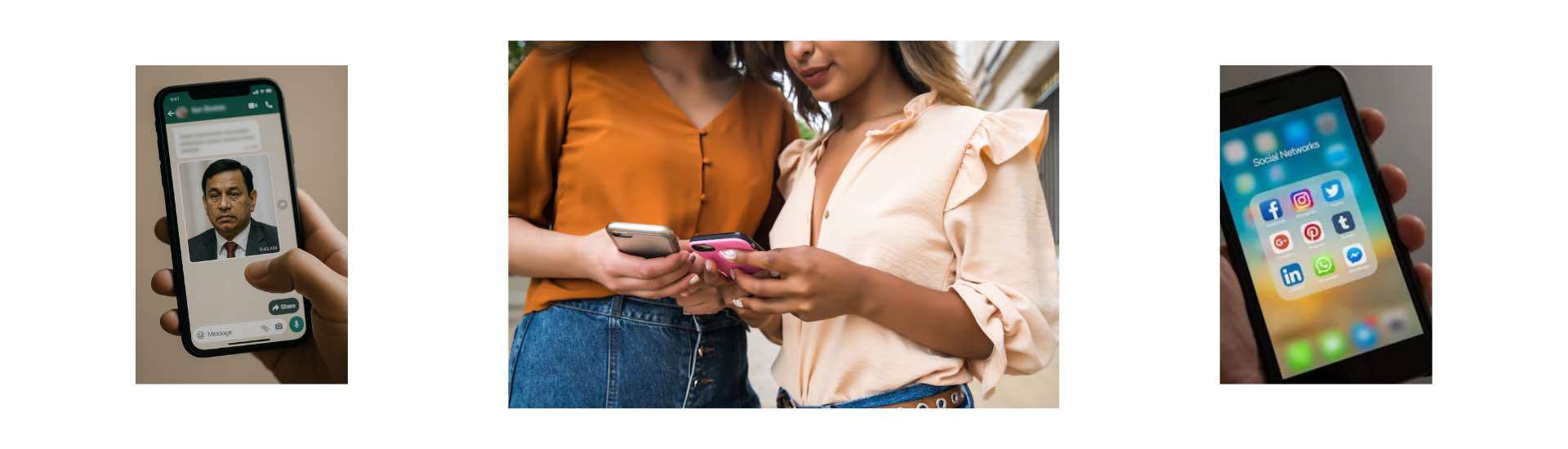

It began with a single photo. A doctored image of Public Security Minister Ananda Wijepala surfaced online last week. By the time the Ministry denied it and the CID announced a probe, the picture had already taken on a life of its own. WhatsApp groups buzzed with speculation, timelines filled with commentary, and the fake had travelled further than the fact.

This is not unusual. In Sri Lanka, as elsewhere, misinformation has found its most fertile ground on social media. A manipulated image of a protest, a misleading headline about a celebrity, even a rumour of school closures spreads faster than any official correction. The problem is no longer just the content itself, but the way we consume it. With AI, the issue is exacerbated.

Why we believe before we check

There’s a reason fake news is so persuasive. It plays to what we already suspect. If you mistrust a politician, a fabricated photo confirms your bias. If you are anxious about safety, a false story about crime validates your fears. And if a headline makes you laugh or gasp, the temptation to be the first to share it often overrides the instinct to verify it.

Psychologists call this confirmation bias. Social media calls it “engagement.” Platforms reward the content that provokes the strongest reactions, like outrage, amusement, and fear, while accuracy struggles to catch up. The result is a culture where misinformation isn’t just a glitch in the system, but a feature of how the system works.

Not Just Our Problem

Globally, the damage is well documented. Deepfake videos have appeared in political campaigns in the U.S., rumours spread through WhatsApp in India have triggered mob violence, and Europe has scrambled to legislate against AI-driven misinformation.

Sri Lanka is not insulated. In 2018, false stories spread on Facebook fuelled communal violence. During the pandemic, conspiracy theories about vaccines ricocheted through WhatsApp groups, often carrying more weight than official health advisories. And now, with AI tools available at the swipe of a screen, the potential for manipulation has only multiplied.

In March this year, the Central Bank had to issue a formal warning after AI-generated deepfake videos misused the CBSL Governor’s likeness to promote fraudulent investment schemes. Around the same time, fact-checkers exposed fabricated social media posts that falsely showed politicians and public figures endorsing “quick-return” investment opportunities. The pattern is clear: misinformation is adapting to the technology of the moment, and Sri Lanka is very much part of the global experiment.

Laws vs literacy

Sri Lanka has not ignored the problem. The Online Safety Act, passed earlier this year, gives authorities broad powers to remove harmful content. The Personal Data Protection Act aims to safeguard privacy in a digital world. But laws alone are not enough. Regulation moves slowly, while misinformation moves at the speed of a tap. Enforcement is patchy, and critics argue that such laws risk curbing free expression as much as they protect truth.

That leaves us with something harder but more urgent: digital literacy. Just as we once taught people to question advertising slogans or political promises, we now need to teach ourselves to question what we see on a screen. Does the source exist? Is the photo traceable? Is it too neatly aligned with what I want to believe? These questions are not second nature yet, but they need to become so.

The erosion of trust

The danger is not only that fakes mislead in the moment. It is that they chip away at trust over time. A false image may be deleted, but suspicion lingers. If enough falsehoods circulate, people start to question even genuine reports. Trust in institutions, in media, and even in one another becomes fragile.

In Sri Lanka, where gossip culture has always been a part of social life, misinformation thrives because it blends seamlessly with the stories we pass around every day. What was once chatter at a tea boutique now travels through Twitter threads and TikTok edits, amplified to thousands. The difference is that a rumour overheard in person fades quickly; a digital rumour leaves a permanent footprint.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The incident with Minister Wijepala may soon be replaced by the next viral controversy, but the underlying lesson should not fade as quickly. In the AI era, misinformation is not an occasional nuisance; it is an everyday hazard. Combating it requires more than official denials or criminal investigations. It demands a shift in how we, as citizens, consume and share information.

The responsibility is collective. Media organisations must slow down and verify before publishing. Fact-checking groups need more support to meet the scale of the problem. And ordinary users, those of us forwarding memes, retweeting headlines, and posting stories, must recognise our own role in fuelling the spread.

Because the true cost of misinformation is not only the scandal of a single fake photo. It is the erosion of the one thing every society needs to function: trust. And once that is lost, no correction, no probe, and no press conference can easily restore it.

0 Comments