Nov 28 2025.

views 577From schoolboy scrum-half to pioneer administrator, the story of a man who lived every facet of the game.

By A Special Correspondent / Pics by Nimalsiri Edirisinghe

Brigadier J.P.A. ‘Japana’ Jayawardena (Rtd) leans back and smiles as he reflects on a lifetime immersed in the sport he loves. “I have lived rugby in every sense,” he says. “Player, coach, selector, referee, administrator, promoter – I have done it all. Not many can say they have gone the full circle.”

That circle began in the 1960s at Trinity College, Kandy, where rugby was more craft than collision and where his small frame and sharp agility earned him a place at scrum-half. Trinity’s boarding school routines shaped him early. Rugby began in earnest at Under-14 level, and by Under-15, he recalls, “my main task was to take the ball and run. With my small size and agility, I was able to slip through gaps and score.”

“Those days, there was no Under-12 rugby. In the junior school, we played football. But once we came to the upper school, we of course had inter-house rugby – that started from Under-14 level,” begins Japana.

“Then, Under-15 was really our first exposure to proper rugby at school. All of us boarders were required to go for sports in the evenings. There, we were taught how to handle the ball and based on our build and stature, we were positioned in different roles. Our prefect, Chulika de Silva, was the one who put me as scrum-half for the Under-15 team, Glenn Van Langenberg as stand-off, Ajit Abeyratne as number eight, Gogi Tilakaratne was flanker, and the other flanker was Sundaralingam,” he adds.

Interestingly, they all continued in those same positions for the Under-17 team, the First XV, the Sri Lanka Schools team – and later on, even at club and national level.

“My rugby career started when I began playing rugby at set practice – my main task was to take the ball and run. With my small size and agility, I was able to slip through gaps and score. That ability brought me some recognition early on,” he chuckles.

“I used to go early for practices, just to play with the ball and improve my passing. Everyone said, ‘You are short, but you can pass the ball well’. That made me determined to improve,” says Japana.

“One day, Marathelis our ground boy, who helped me practice, showed me a technique – he placed five barrels around me and told me to stand in the centre and hit the empty barrels one by one. I’d throw five balls, go collect them, and repeat. That’s how I developed my passing accuracy,” recalls Japana.

“Even at Sri Lanka level, I was known for a long, direct pass – sometimes bypassing the stand-off and sending it straight to the first inside, which confused opponents and created dummy plays.”

“The dive pass was the most important skill then. You could send the ball exactly where you wanted, and the opponent couldn’t hit your hands – only your legs. Nowadays players pass standing up and get hit on the arm, and three quarters get a delayed pass,” he says.

“I practiced the pivot pass too – turning and sending the ball quickly. The key in dive passing was avoiding your opponent’s interference and sending a clean, long pass to your three-quarters,” he adds.

“By the time we played Under-17, all of us were in our regular positions. Our captain was Prasanna Jayawardene, a very good leader who led us to an unbeaten season throughout the entire school tournament. Hilary Abeyratne was our coach,” he recalls.

“When I came to the First XV, my position was already occupied by the captain, M.T.M. Zaruk, who was also the scrum-half. I couldn’t displace him, so I had to wait. During that period, I took up hockey instead, and ended up representing both school and Kandy District that year,” he said.

When Zaruk left school, he returned to rugby in 1966. “That was my first year playing for the Trinity First XV, and I was awarded a Lion that very year. To earn a Lion in your first season was something rare; it had been ten years since anyone had done that. The previous being Gamini Weerasinghe,” he shares.

“That year, Isipathana was a big challenger. They had an excellent team and came to play us at Bogambara. A whole trainload of supporters came from Colombo expecting Isipathana to win. They scored first with a cross kick to their wing three-quarter, but we came back strong and beat them 26–3 or 26–5,” he recalls.

“I was concussed in that match and carried off midway through the second half, but later returned to play the Bradby Shield. In the first leg, Royal led through a penalty by Jayman (three points, same as a try in those days). In the dying moments of the second half, five yards from the line, I scored the try that drew the game. Then in Kandy, we beat Royal 12–3, and won the Bradby Shield that year,” he recalls.

Percy Madugalle was Trinity’s first XV coach. “Those days rugby was simple: one fitness trainer, one coach. We were taught discipline – how to play clean, gentlemanly rugby. There was no organised cheering, no music, no media interviews. Only the coach or master-in-charge could speak to the Press. Even Lions could lose their award for misbehaviour – some had them withdrawn and re-awarded later depending on conduct. That discipline defined us,” he relates.

“After our school season, Glenn and I were once selected to play for Upcountry, but the Trinity Principal C.J. Orloff didn’t allow us, saying we were too young to play with adults. He was strict but principled,” he adds.

Memorable People

“Our bus driver, whom we fondly called ‘Bus Banda’, was one of our biggest critics and supporters. After matches, he’d analyse our play – ‘You didn’t tackle. You didn’t pass quickly enough. You avoided the ruck’. His criticism was constructive. On the way back from games, he’d debrief us before the coach even did!” he recalled.

“I’ll never forget the day I got my Lion. I was on prefect duty supervising junior boys upstairs when Bus Banda came running and shouted, ‘Sir! Lion!’ I thought he was joking and told him, ‘Don’t talk nonsense’. But it was true – I had won my Lion in my very first year,” he recalls.

Joining the Army

After playing for Havies (1967–1969), he joined the Sri Lanka Army in 1970. “I was encouraged by Brigadier P.D. Ramanayake, who scouted sportsmen for the Army – athletes, boxers, Olympians like Wimaladasa, S.L.B. Rosa. He took me to the Army Commander, who laughed and said, ‘You may be short, but you’ll be commanding men six feet tall – don’t worry!” recalls Japana.

The Army gave him huge encouragement. “General Sepala Attygalle, the Army Commander, supported us and was proud when we won the Clifford Cup twice during his tenure – once against Police (19–19) with S.P. de Silva as captain in 1973, and later in 1975, when we beat Air Force when Saliya Udugama was captain,” he said.

“We were coached by Berty Dias initially, and later by General Sena Sylva and Denzil Kobbekaduwa – both were inspiring mentors. Col. Kandiah handled our fitness, and General Seneviratne chaired rugby administration. Other notable supporters included Brigadier Halangoda, who was very keen on developing Army rugby, and General Thurairaja, who ensured injured players were treated immediately – he bypassed red tape to take care of us. His superior, Thambiah of the Medical Corps, was also a great supporter of sportsmen,” said Japana.

Army Rugby and Teammates

“Our captain was Bashoo Musafer, with S.P. de Silva – a double international in rugby and soccer – as vice-captain. Others included Rodrigo, Edwin, M.F. Fernando, and Ruperatne Weerasinghe, Amaradasa, all strong forwards, most of them PTIs and athletic men,” he said.

“Only a handful of us – Bashoo, Saliya Udugama, Malwatte, Ganja Mohamed, Jayantha Weerasinghe, P.G. Gunawardena, Gunadasa and myself – had played rugby before. But we built a great team spirit, and eventually many of them represented Sri Lanka,” he says. Japana played for the Army until 1981, making it about 14–15 years of club rugby, from 1967 to 1981.

National and International Rugby

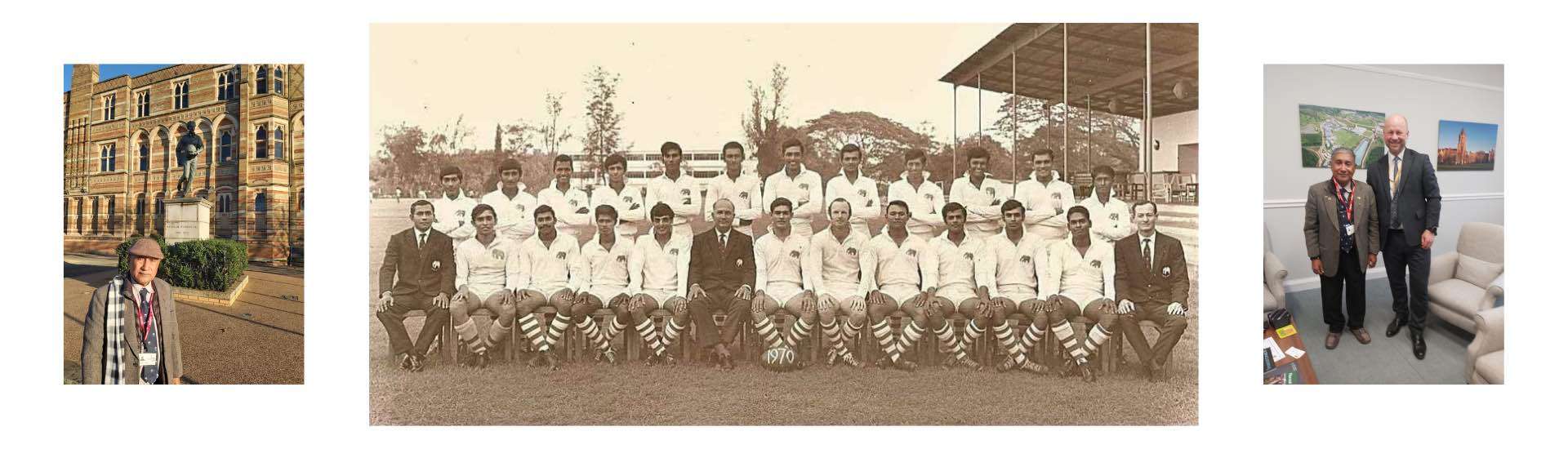

Japana first played for Sri Lanka in 1967 at the All-India Tournament. Later, he represented Sri Lanka against several foreign sides such as Bosuns (UK), Combined French Universities, Japanese National Team, London Welsh, The Far Eastern Defence Services and many All-India Tournaments.

“The nickname ‘Japana’ came from my initials – J.P.A. Jayawardena – and my small build. In the boarding house, everyone had nicknames. Because I was small, quick, and ‘Japan-built’, they started calling me ‘Japan Bonika’. From there it became ‘Japana’,” he says.

Reflections

Rugby shaped his entire life. “Though small in stature, I was always encouraged to do bigger things – to play against men double my size and still hold my own. That encouragement from school, my coaches, and my teammates gave me the confidence to achieve everything I did – in rugby, in the Army, and in life,” he says.

He was coached by Dr Larry Foenander in his first year at Havelocks. In 1967, the captain was Gamini Fernando. The following year, 1968, the captain was Noel Brohier and Darley Ingleton as coach. In 1969 it was Jeyer Rodriguez as captain Nimal Maralande as coach. “When we toured Thailand in 1970, the Sri Lanka team was coached by Kavan Rambukwella. Cdr Eustace Mathysz chairman,” he adds.

“The Army Commander at the time Gen. Sepala Atygalle was very supportive. In fact, several Army Commanders over the years played a key role in encouraging rugby. Generals Dennis Perera, Tissa Weeratunga, and Hamilton Wanasinghe were all deeply involved in promoting the sport. General Wanasinghe was particularly keen, and on his request I coached Ananda. His brother also played for the Army and later represented Sri Lanka as a forward. There were others too — General Cecil Waidyaratna, General Jerry Silva – all of whom gave tremendous support to Army rugby,” says Japana.

“Later, General Rohan Daluwatte, himself a fine sportsman and basketball player, continued that tradition. As chairman of Army rugby, I was fortunate to have his encouragement to bring in foreign players and coaches. After we played London Welsh, I established connections there, which allowed us to invite coaches and players from Wales to train the Army team,” he adds.

“Following General Daluwatte, under General Srilal Weerasuriya, we brought down Coach Kelvin Ferrington from Australia through the efforts of Dilip Kumar and Jayantha Weerasinghe, both based in Australia at the time. Jayantha, who had coached the Army before emigrating, was a former Secretary of the Rugby Union. With Ferrington’s guidance, we achieved remarkable success, defeating several top clubs. He was an Australian league coach and introduced a new level of professionalism,” says Japana.

“Afterwards, General Balagalle also gave immense support. Throughout these years, as Chairman of Army Rugby, I always had the full backing of the commanders. Without that, it would have been impossible to run training camps, motivate players, and build a cohesive team. Our emphasis was always on teamwork – mixing officers and other ranks so that everyone played as one unit. This unity was key to our success,” he adds.

“We reached the finals many times, sometimes losing narrowly – against teams like CH & FC and CR & FC – but those achievements were commendable considering we were operating during wartime. Despite the ongoing conflict, we continued to play and maintain discipline and spirit. Today, with no war and all facilities available, the Army should ideally be performing even better across all sports, not just rugby. Unfortunately, the same level of encouragement and leadership is lacking,” he points out.

As Chairman of Army Rugby, Jayawardena pushed boundaries. Leveraging friendships with London Welsh players, he brought down foreign coaches from Wales and Australia. The most transformative was Australian Kelvin Ferrington, secured with the help of Dilip Kumar and Jayantha Weerasinghe.

“Kelvin transformed our play,” he says. “We beat top clubs. It showed what exposure and good coaching can do.”

“I must also acknowledge the past rugby chairmen who contributed immensely before me – people like Brig. Halangoda, Brig. Ramanayake, Brig. P.K.B. Perera, Brig. C.J. Abeyratne, Brig. Frank Silva, Brig. Gnanaweera, and Brig. S.M.A. Jayawardena. After my tenure, Brig. Krishnaratne became chairman and continued the good work,” he said.

“Together, we also focused on developing local talent. Rather than depending solely on foreign players, we sent several Army players to Wales for advanced training – including P.G. Gunawardena (flanker), Dharmapala and Waduge (top forwards), and Wijesiri (fullback). We also sent Capt. Marasinghe as team administrator. Later, Lt Col Gunasekara served as Secretary of Rugby under Krishnaratne,” he noted.

Referees Society

After Metha Abeygunawardena and Ana Saranapala, Japana took over as Chairman of Referees Society in 1997 for about two years. “We made it a practice to hold annual conferences between referees and coaches to interpret new laws together. These meetings, held twice a year, ensured consistency and avoided disputes. We also invited international referee assessors to evaluate and train our officials, and some of our referees were later sent abroad – to Ireland, Scotland, Wales, France, England, Australia and Singapore – to gain exposure,” he says.

“Refereeing is not just about knowing the laws; it’s about managing 30 players on the field. Mistakes happen even at the highest levels, but the goal is always to minimise them. Complaints must be formal and evidence-based – not gossip,” he said.

He points out that Bradby Shield matches were often refereed by old boys of the two schools. “For instance, Commander Harry Goonatilleke, a Royalist, refereed a Bradby; so did Miles Christofelz, Bertie Dias, Denzil Kobbekaduwa, and Mahes Rodrigo. Interestingly, referees were usually stricter with their own school’s team, ensuring fairness. Mistakes were accepted as human errors, not intentional,” he said.

He is passionate about the five links that sustain rugby: players, coaches, referees, administrators, spectators. “If one link fails, the game suffers,” he insists.

He also calls for urgent reforms: random drug testing, spectator education, and non-contact mini rugby for children. “Parents will support the game if early rugby is safe – running, passing, kicking, not tackling.”

“If one link fails, the game suffers. Spectators too must be educated on the rules – through TV programmes, discussions, and demonstrations –as done abroad. Everyone involved should understand the laws and their interpretations,” he said.

“We must also address issues like drug use in sports. In other countries, random drug testing is common – even during practice sessions. I believe Sri Lanka should adopt this system to maintain integrity,” he stressed.

In terms of administration, during his era – from 1967 to 1982 – Rugby Union presidents generally served for one or two years. “Each knew his successor in advance, ensuring smooth transitions and continuity. None interfered after stepping down. I too followed that principle, believing young administrators must take over while elders offer guidance, not control,” he said.

The following distinguished gentlemen held the high post of President of the CRFU/SLRFU during his time: Dr W.D. Ratnawale, Dr K.B. Sangakkara, Cdr EL Mathysz, Capt. W. Molagoda, E.L. Vanlangenberg, M. Bostock, S. Navaratnam, S.B. Pilapitiya, K. Rambukwella, Lt Col Mahinda Ratwatte, N.H. Omar, Y.C. Chang, Lionel Almeida, Malik Samarawickrama, Rudra Rajasinham and Gamini Fernando.

“Now, with the return of structured governance under World Rugby (IRB) guidelines, I hope the current administrators continue to strengthen the game. Sri Lanka, after all, has a proud rugby heritage of over 150 years – our Rugby Union was formed even before South Africa’s, by a year,” he adds.

A pioneer of women’s rugby, he was directly involved in its early development. “While commanding a regiment of 2,500 men, I was also placed in charge of 5,000 women under my command. When the Women’s Corps was formed under General Denis Perera, I encouraged the formation of a women’s rugby team. We began by organising matches between the A and B teams, later joined by Police and CH & FC women’s teams,” he said.

He also pioneered the Central Provincial Referees’ Society, bringing a Referee Coach from Sydney to train referees in the region. Later, while serving in Anuradhapura in 1994, he organised an exhibition game featuring school players from Trinity to introduce rugby to the North Central Province. That effort later grew into a full-fledged regional rugby union under Lt Col Dhammika Gunasekara. He also worked with the Navy for several years on rugby development programmes.

He believes Sri Lanka should introduce non-contact mini rugby for children, as done in the UK – focussing on ball-handling, running, and basic skills. “These games develop coordination and understanding of rugby without the risk of injury. Parents would be more willing to encourage participation if the early stages emphasise fun and safety. Through such initiatives, we can build a strong foundation for the future of Sri Lankan rugby – from the youngest age groups to the national level,” he opined.

“Looking ahead, I’ve always felt that, considering our physical build and our place in South and Southeast Asia, Sri Lanka should consider developing weight-class rugby, similar to boxing. That would allow fairer competition among players of similar size and weight. Recently, some countries have introduced 80-kg and under categories, and I believe we could adopt a similar structure. Dilip Kumar as Australia Rugby Chairman invited the Army team to play 80/80 rugby tournament in Bangkok some years back,” he said.

“At the same time, we must also focus strongly on rugby sevens. Our players are naturally agile, quick, and skilful – perfect attributes for sevens. That’s an area where Sri Lanka can truly excel,” he said.

Jayawardena laments how modern rugby has evolved. “In our time, rugby had a certain beauty – we worked the ball through the three-quarters, created loose play, and used our skills. The wings had space to run; the crowd loved the scissors moves, the dummies, the cross-kicks, and the punts. Today, you rarely see those. The modern game has become more physical – hit after hit, ruck after ruck, with frequent turnovers. It’s effective, yes, but the artistry, the flair of open running rugby, has largely disappeared,” he opined.

“In our days, even lineouts were different – you weren’t allowed to lift players. The second-rowers had to jump on their own, relying purely on timing and skill. So height alone wasn’t an advantage. Now, the laws have changed, the strategies have changed, and so has the spirit,” he adds.

“Sadly, the gentlemanly approach we once valued so much has faded too. Many play to win at any cost. Spectator enthusiasm has also declined, except at school matches, which thankfully still draw passionate crowds. If we want to revive rugby’s full glory, the five key links must stay connected – players, coaches, referees, administrators, and spectators. If even one of those breaks, the game suffers. Ultimately, rugby itself must be the winner –not an individual, a club, or a faction,” he said.

“Administration must always be fair and forward-looking. There should be healthy competition among clubs, and everyone should work toward the greater good of the game,” he noted.

On a personal note, he was privileged last year to visit the Rugby School in England, the birthplace of the game itself. “It’s in a small town called Rugby – even the railway station and the school bear the same name. The CEO received me warmly. It was a great honour to walk on that very ground where, in 1823, young William Webb Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it, changing the course of sporting history. I even spoke with the students and shared lunch with them. It reminded me so much of Trinity College – a traditional, boarding-style environment. Visiting that sacred place felt like completing a full circle in my own rugby life,” he recalls.

Jayawardena sees his career as proof that size never dictated destiny. “Though small in stature, I was always encouraged to do bigger things,” he says. “That encouragement shaped his Army career, his leadership style, and his approach to life.”

“When I look back, I realise I have experienced every facet of the sport – as player, coach, selector, administrator, referee, and promoter. I have worked to develop rugby across provinces, from the Army to Anuradhapura and the Central Province. The following Army officers assisted me in developing Rugby in the North Central province: Maj. Gen. A.M.U. Seneviratne, Lt Col Sunil Ranasinghe, Evan Chandrasekera and Keerthi Ekanayake. I helped start the Central Provincial Referees’ Society and introduced the game to schools in the North Central region. I’ve also had the privilege of representing Sri Lanka abroad – visiting Japan, Singapore, and Malaysia on official Rugby Union matters – as one of the first Sri Lankan rugby representatives to be received at that level,” he said.

He continues to keep ties with London Welsh – especially former captain and current president John Taylor – a friendship forged decades ago.

“Even now, I maintain close connections with Wales and London Welsh. I first befriended their members after our match with them, and every time I visit the UK, I meet with them. The London Welsh President, John Taylor – once their captain – has always welcomed me warmly at the Richmond Club,” he says.

“On one visit, I even sourced a coach from Wales Wayne Hall (hooker for Wales international side) who came here to coach Army some years back. Mohan Samarasinghe assisted me in this regard. Meanwhile, a highly experienced trainer who had coached the Welsh women’s national team and was coaching a club side there was also recommended by me to the Army Commander this season,” he adds.

Near the end of his reflections, his voice softens. “I wish to thank my parents for encouraging me to play rugby football in school,” he says. “Their belief in me gave me the confidence to pursue the sport with passion.”

He adds a final tribute: “I also want to express my gratitude to Chrishanthi, my wife… her unwavering support and understanding have been invaluable in my long rugby career.”

Looking back on six decades in the sport, Jayawardena’s wish is simple: that the game remains bigger than any individual or institution.

“In the end, no matter who plays, who wins, or who chairs – rugby itself must be the winner,” he says.

Few have lived that philosophy as completely as he has.

0 Comments