Mar 09 2022.

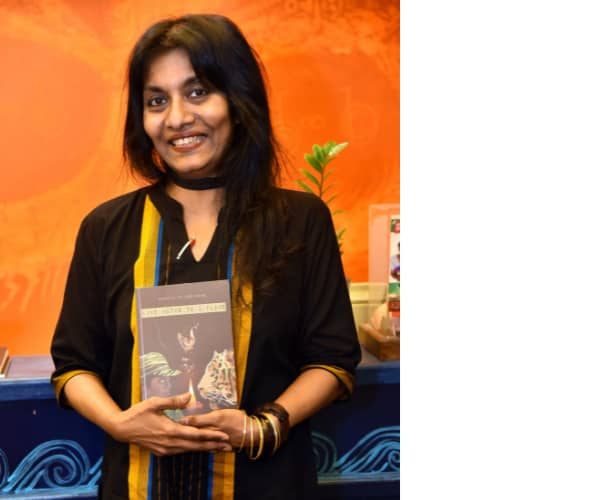

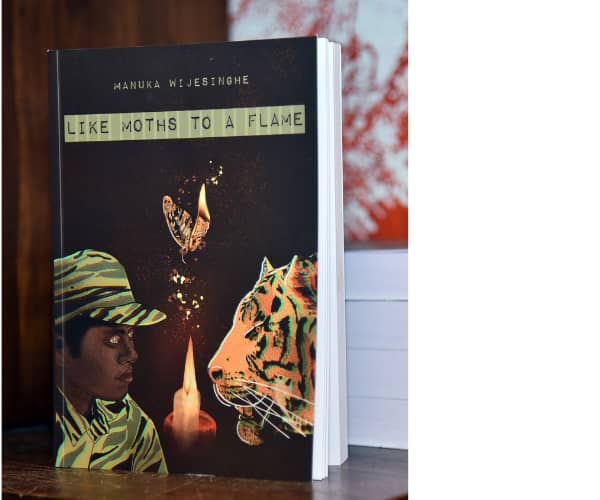

views 382The voices and thought processes of Saraswatiammas, Bawas, Velupillais, and Parvatiammas have been brought back to life. Juggling between the various castes of Hinduism and a long-lost poetic culture, Manuka Wijesinghe explores the nature of man, his faith, speech, desire, diversity, and cultural priorities in her latest book ‘Like Moths to a Flame’. The book tells the story of one family and their life in the present while being bound to prisons of past experiences.

This book is more or less a tribute to her father. “I started writing this book shortly before my father died, when he was going through this process, from becoming a Socrates-like figure to becoming a child,” recalled Wijesinghe in an interview with the Daily Mirror Life. “I had to write something which had no calculated reason. I knew he was going away and I wanted it to be portrayed in some kind of beauty. He was a very rational person and had a big influence on my life. This book has no rationale and reason but is more mystical and flowery. I was here in January 2015 and was learning about Sangam poetry and it took me about five years to complete.”

Her journeys to the war-torn areas had come in handy when penning this masterpiece. Interwoven with Sangam literature, the various castes ‘superimposed’ by Hinduism and the differences these castes have created among humans have been cleverly portrayed in the book. She believes that the fact that she learned Tamil and her relationships with people of the North and East made it easier to connect with them and understand what they were going through.

“I have been to all those war-torn areas and was learning Tamil as well. I read and write Arabic and I know how these languages work. I studied Islam many years ago, sometime after the Iranian revolution and while I was studying Islam, I started studying Arabic separately. It’s a beautiful language and it opens up like a flower and has an absolute contrast to Tamil which is cut and dry. It was through language that I was trying to understand people and I have met every single person in this book. From the plantation worker to the Velupillai type, the Jesuit priest, Portuguese Burgher, etc., I spent a lot of time in the North and East to write this book. I managed to get to these areas after I wrote Monsoons and Potholes for readings and they used to tell me things that they wouldn’t tell a normal person. Knowing the language helped me to understand. Speech and mind have a connection. This book I would say is not like other books where I didn’t depend at all on what was published so far. I only referred to the Sangam poetry. I just had myself and the computer.”

Certain dialogues she had with her father have been reflected in the form of questioning love and understanding the presence of (a) God. “During the final days of my father’s life, I had to teach him to appreciate beauty. He is someone who would blankly question what beauty is,” she recalled.

In order to understand God, Wijesinghe turns to studying the principles of Platonism. “We have fought a war for 26 years and we talk about a rise in Sinhalese, Muslims, etc. But what’s the point of talking about a rise if we can’t live together? It’s a community of brotherhood that a lot of parties are trying to destroy. I needed to understand God because I felt that we have to transcend. We have been destroyed by reason; individual rights and we are incapable of transcending. To transcend we have to come together on one concept of God. This should be something beautiful like the capacity to admire a beautiful flower. I come from a culture where I have no personal God. Therefore, In order to understand the sense of God I went back to studying Plato; went back to Greek philosophy. I had to understand it from the mind. I’m naturally not this ecstatic person so I couldn’t understand this kind of devotion, opening, giving yourself to something as a Muslim would do who believes in God. I understood the devotion, opening, and giving yourself to something as a Muslim who believes in God would do through Platonism, through the archetypes, forms, and attributes and it was through this that I was able to create characters, especially the Bawa. I had met a lot of Sufi and they have told me their stories but I had to go into the skin of a person. It was through Platonism that I was able to go into their skin.”

The book includes several sections inspired by Sangam poetry. Apart from that, most of its characters are Tamil and Muslim. Sangam literature spans across a Dravidian landscape, especially South India. “It has different poetic landscapes from Kurinci which is the forest areas where falling in love is like hiding behind a tree and coming out, the Marutham is like a lagoon area where love is like the beak of a kingfisher piercing through a fish. In all these areas the poetry includes flora and fauna, God and love are according to how the landscape is. I felt that we lived in a Dravidian poetic landscape and Hinduism superimposed and brought in the caste system. I realised that Hindu society is extremely fragmented by caste. At one point Velupullai gets a job in the East and I bring the difference between Northern and Eastern Tamils. In the East, sons don’t own property and they’re free to fight. But in the North sons own property and they have more to lose. I brought the element of Portuguese Burghers because they were hilarious. They were daily labourers who were never interested in education. They wanted to work and have a good drink at the end of the day because women had all the money. The character Sri was inspired by the late journalist Taraki Sivaram and his incident.”

While revealing the differences among the cultures, Wijesinghe points out that at one point in time, the statue of Buddha and that of God Pillayar were sitting side by side. “In the 1950s Buddha statues were under the shade of trees in the East along with the pantheon of Hindu Gods. This was told to me by a Catholic priest. But they were later removed and were made our sole property. Therefore it looks like the whole thing was planned. Neville Jayaweera’s books portray these incidents. I think we wronged the Tamils and as a Sinhalese, I feel guilty. We are at fault and we let it happen and we are paying for the sins. But ironically or otherwise, today we see more Buddhists visiting kovils and worshipping Hindu gods.”

Even though an umpteen number of books have been written about the war and its aftermath from various perspectives, textures, and flavours, reconciliation between the two ethnicities seems to be a distant dream.

“We need to work at the grassroots. Reconciliation should be brought about from schools. School history is identity politics. We would be far better if we had no schools. We will teach our children common sense, ethical conduct, civics, faith, and brotherhood and parents are capable of that. In school, I had Tamil and Sinhala medium. We have to do a lot more. I remember one of my father’s friends saying that we have never been able to protect our minorities. He said it with much anguish and those lines I have always kept. Therefore I wanted to be a mouthpiece of the minorities. I’m doing it because my birthright has given me the courage to do that.”

Wijesinghe observes the importance of learning Tamil as a language as well as the Tamil culture if the “minority” and the “majority” need to find some sort of connection. “Buddhism isn’t an island monopoly. Faith is about sharing. I grew up at a time where during Christmas we go to the homes of our Christian and Catholic friends and during Ramadan we eat watalappan. We have always shared our faith. Then a certain cultural body decides to separate Buddha from the rest of Ceylon’s people and we haven’t had the intellect to protest about it.”

In a parting message to aspiring writers, Wijesinghe said that they should go as far as they can with language. “Play with sounds, language, etc. Language is such a vast thing. You can create new things with language. Be creative and don’t stick to academic dictates. You won’t become a writer with a university education. Be skeptical of people who try to shift your position. Have faith in yourself. People are very envious and they don’t want the better person to come out. Be objective with yourself. When you write something freeze it for one year and then go back. Take opinions from people but all of them are subjective. Understand people before writing dialogues. Make sure that you find a good editor. After all, writing is a wonderful exit.”

Pix by Kushan Pathiraja

0 Comments