Nov 22 2022.

views 1200A cozy abode bordering a paddy field amidst an abundance of greenery in the heart of Athurugiriya is veteran contemporary artist Pala Pothupitiya’s workshop cum resting space, aesthetically designed by the late artist extraordinaire Laki Senanayake. Despite his simple lifestyle, Pothupitiya has placed Sri Lanka on the world map with his various artworks which questions caste-based differences while confronting issues such as colonialism, nationalism, religious extremism and militarization. His works are also an attempt to generate a critique of Euro-centrism in the postcolonial setting. Born in 1972, Pothupitiya hails from Deniyaya and has earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree from the University of Visual and Performing Arts.

Pothupitiya draws inspiration for his artworks from his father, Somaweera Pothupitiya. His early memories are of his father stitching decorative pieces of art, designing costumes, decorating streets for the Matara tradition of low country dancing. At his hometown in Deniyaya, he used to design clothes alongside his father. “I then shifted to Matara to do my A/Ls and later got selected to Heywood College of Fine Arts,” said Pothupitiya in an exclusive interview with the Daily Mirror Life. “Here I got to know various people. The Heywood had no walls around it and everybody involved in arts to drama would come to the college to have a cup of tea. I have seen them until I left the college and regular conversations with them helped me improve my knowledge. One of my mentors was Jagath Weerasinghe who inspired me to portray an idea, life experience or feeling as a form of art. He was a pioneer in bringing about the ‘90s trend’ along with the ‘Theertha Artistes Collective’. It is around this time that I got addicted to the arts.”

His final year project was to project how Western art highlighted Eurocentrism as a superior force. “Therefore, traditional forms of art were looked down upon as underdeveloped and primitive genres as means of suppressing them. One thing I have seen in contemporary art is where art researchers and curators study about these so-called primitive forms of art, thereby suppressing them further. Certain aspects of traditional dance genres still exist and they are living traditions but critics and art researchers would say that these dance forms had more value back in the day. Such thoughts suppress the expression of these dance forms and projecting them to be witnessed through a modern lens. So I took a keen interest to study about how colonial influences teach us to suppress ourselves through various institutions.”

Pothupitiya is a founding member of the Theertha International Artists Collective. In 2005, he was selected to participate in the Third Fukuoka Triennial at the Fukuoka Art Museum in Japan, and in 2010 he won the jury award of the Sovereign Art Asian Prize, Hong Kong. He has participated in many local and international art exhibitions and events including Colombo Art Biennale (2012), Colomboscope (2013), Serendipitiya Art Festival, Goa (2015), Inaugural Karachi Biennale, Pakistan (2017) and Museu d’Art Contemporanide Barcelona, Spain (2019) to name a few. His works are in the collections of Fukuoka Art Museum, World Culture Museum, Germany, Vina Museum, Austria and Museum of Contemporary Art, Barcelona, Spain. Pothupitiya is of the view that schools condition children to become racist, feeding them to consider Eurocentrism as a supreme force. “My father has never been to school, but he’s not racist. But once I started going to these colonial institutions I was being taught that Sinhalese is a majority race deliberately making me look down upon another race. On the other hand, institutionalized Buddhism is accompanied by political power. So I try to highlight these colonial elements in my artworks.”

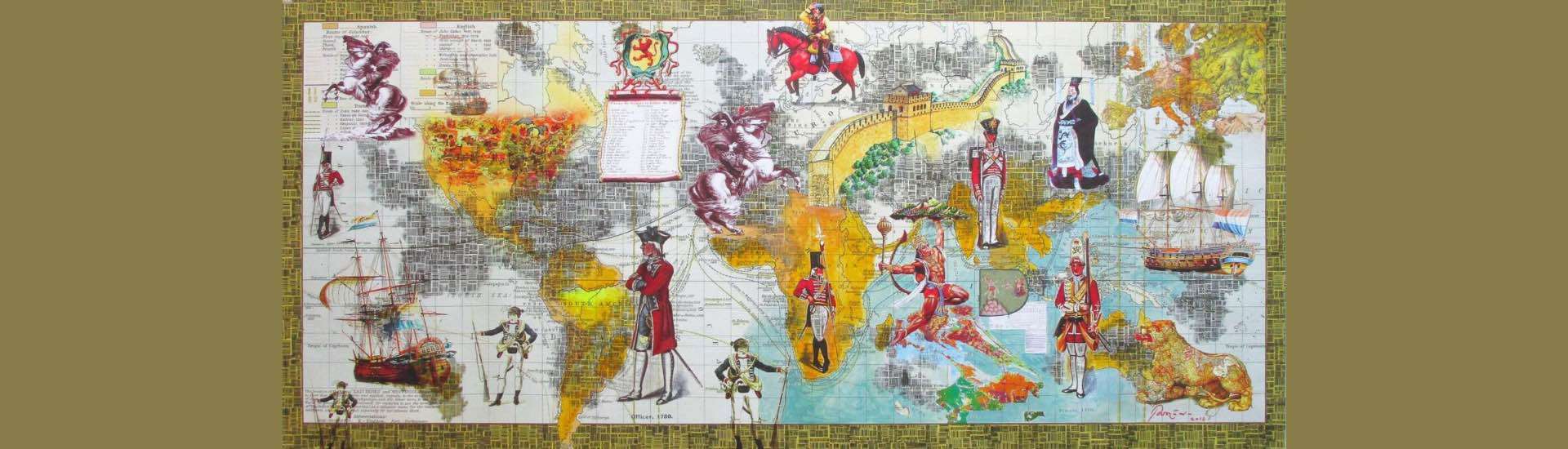

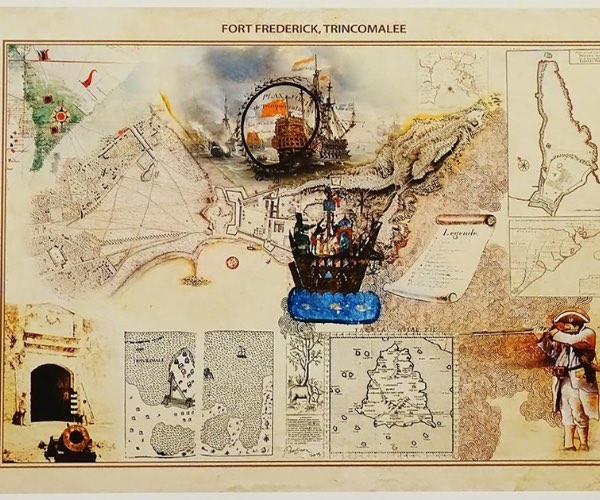

Pothupitiya is known for his unique way of reconstructing of maps where he portrays these colonial elements in a more subtle manner. He defines a map as a powerful tool that portrays colonialism and colonization. “Colonialists have mapped colonization, trade and cultural colonization. Our map has been designed by colonialists,” he added. His earliest works of map art included reconstructing Sri Lanka’s district maps into figures of lions and tigers. He says that maps separate people, similarly to separatism which was one of the fundamental reasons for the 30-year ethnic conflict. “This conflict was engineered by those in the powerful social class but the victims were the underprivileged, innocent youth in rural settings. People in the South and North were equally affected by the conflict. But the issue is that most events done in Colombo give more prominence to people in the North and the Tamil-speaking community. Many are of the view that only those in the North were impacted. But those in the South too were affected. We shouldn’t show the divide between the North and South. This is what I try to show through map art.”

“I see global politics as a mafia and through that, powerful forces engineer various conflicts. We receive global support to continue the conflict. Once I reconstructed the world map using the logos of all media channels in the world. Most media institutions have zero ethics. Media wants to sell happiness and sorrow at the same time. Therefore I have less respect for most institutions. The behaviour of religious leaders, political leaders, media have a greater impact on the prevailing crisis.”

Pothupitiya’s aim is to portray global politics and violence through maps. His series of upside down maps of South Asia, titled the Colonial Dress to the various reconstructions of Sri Lankan maps drawn by Ptolemy and other colonialists portray his critique about Eurocentrism in the postcolonial setting. He says he has been successful in his efforts to express his ideas and is proud about the fact that he’s a full time artist. “We have been conditioned to think that an artist is always poor. This is one way of fooling artists so that people can get their work done for a pittance.”

However he has identified a dearth of new knowledge that could have been disseminated from universities. “Even though Sri Lanka’s contemporary art has achieved some sort of recognition, one thing that has to be noted is that the university curricula have not evolved to inspire future generations. There’s no space for art criticism. There’s nothing that happens beyond drawing, painting etc ; there’s no space for concept design.” This is why the Mullegama Art Centre has been initiated since 2011 to disseminate new knowledge about various forms of art to youngsters in his community. He says that this is a more sustainable model as the target group is less and the approach is more people-centric.

“New knowledge is developed in the alternative space. But that again is uncertain. The Theertha Collective has done many workshops but it’s high time for a team of fresh thinkers to take the baton forward.”

Even though traditional artists may sometimes perceive digital art as a threat, this hasn’t been the case for Pothupitiya. In fact most of his maps have been reconstructed digitally. He says it’s the idea that needs to be highlighted. The media is immaterial. “Following the influence of the ’43 group’ there was a time where the urban artist portrayed the rural setting in a very exotic manner. With that there was a change in the expression of ideas through art during the ‘90s. But we are stuck with archaic ideas. There’s a dearth of new, innovative knowledge. Art will prevail but in a more linear form,” he said in conclusion while adding that there are no potential elements as yet, to dilute this linearity.

(Pix-palaart.com)

0 Comments